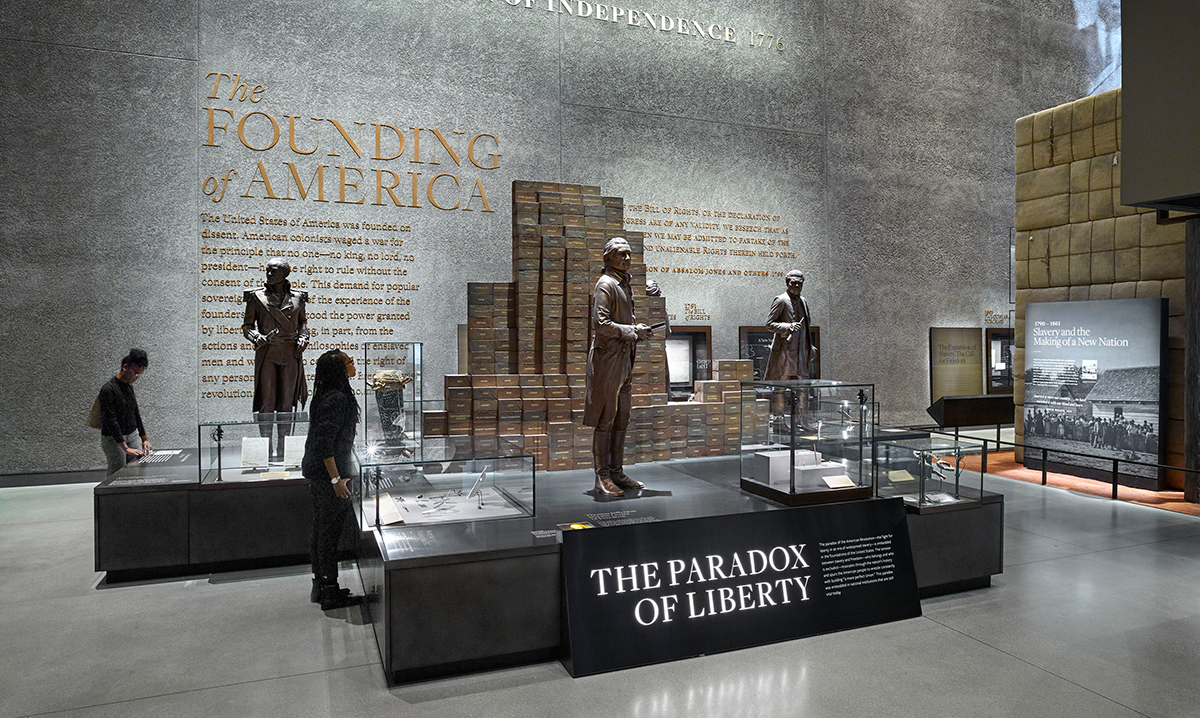

(Akiit.com) The first of September was a bright morning on the National Mall. We went to pay respects to the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

On the top floor, we were greeted by Chuck Berry’s sleek red convertible. Nearby, Odetta sang “Oh, Freedom” at the March on Washington. Marian Anderson performed at the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday. Gospel, jazz and the blues rose from Black culture.

When we walked out from the ground floor, a real slave cabin made a haunting image. Growing gardens around them could help feed a family.

There’s much more in between.

The architectural ascent, from slavery and segregation up to community, music, sports, arts and entertainment, shows a spirit that refused to be conquered. The Rosenwald schools in the South (a private gift) allowed poor Black children, like civil rights champion John Lewis, to be educated.

Remember the day Arthur Ashe won Wimbledon?

The building, made of bronze lace in a trapezoid shape, stands near the Washington Monument. Full of voices telling and singing stories of the nation’s history, and artifacts that don’t let it be forgotten, it opened its doors in September 2016.

Only nine years old, this Smithsonian museum — a testimonial to the Black experience since Transatlantic slave ships started arriving in port cities — opens a new history book, one we never read in class. In the eighth month of Donald Trump’s second presidential term, it’s already in rough high seas.

That lent some urgency to the visit, a protest vote against Trump’s clear and present threat to expunge part of the museum’s exhibits.

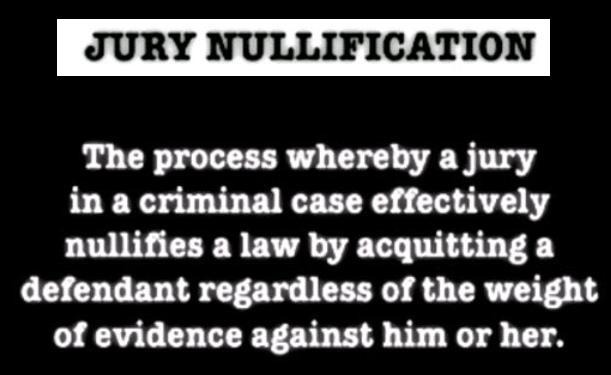

Slavery is on the endangered list; maybe the Civil War and Emancipation Proclamation, for all we know. Abraham Lincoln freed 4 million enslaved people with a single stroke. The brave “Colored Troops” who fought for the Union might be erased.

In a shining grace note, the Lincoln Memorial shrine stands visible in the distance.

As we approach America’s 250th birthday next July, Trump scolds the nation’s memory-keepers for dwelling on “how bad slavery was.”

His scorn for the scar, shocking as it is, should not surprise us. The White House view of Black history comes down to “whatever I want.”

In fact, that’s the motto for Trump’s second term. He railroaded the Republican party and the Supreme Court, fired the librarian of Congress, shut several government agencies, cut public health to shreds and is now breathing down the independent Fed’s neck.

It’s remarkable how fast Trump consolidated power. Then again, it would be better to do it quickly, to paraphrase “The Tragedy of Macbeth.”

What we’ve got to get about Trump, before it’s too late, is that there is no line between his private gain and the public good. The United States of America belongs to him, personally. The rest of us are just background. And he can own history.

The more he exerts raw rule, with fear rising among the least of us, the happier Trump is. That is not the America we know. But that is the America we have become.

Trump would turn the turf on the National Mall into his garish golf club. How convenient that would be.

To murder hard truths of history is even worse than Trump’s seizing the Fed, Congress or the Supreme Court. Those changes ebb and flow over time.

History creates collective memory, embedded in us. The past is, as James Baldwin wrote, “literally present in all that we do.”

But it took America so long to admit our original sin, to see the flaws of our founders — nearly two centuries.

Declaration of Independence author Thomas Jefferson lived a perfect contradiction, owning hundreds of humans, including his mistress and their children, and possessing unalienable rights.

History’s “wrenching pain,” in poet Maya Angelou’s words, can’t be buried alive once again.

No, not after this collection was built from scratch (mostly from family homes) by Lonnie G. Bunch III, now the Smithsonian secretary.

Bunch is the historian who could save racial remembrance from Trump’s wrath. He speaks of major figures like abolitionist Frederick Douglass, denied a chance to speak at the Smithsonian.

From there, the museum mission is to honor the jagged joy of overcoming: “a way out of no way.”

Columnist; Jamie Stiehm

Official website; https://www.jamiestiehm.com/

Leave a Reply