(Akiit.com) The staff at the Los Angeles Free Press was excited in October 1972 when they got word that United Farmworkers of America’s founder and President Cesar Chavez would be stopping by our offices. I was a bit on edge because I was assigned to interview him. My edginess stemmed in part from fear, and in part awe of him.

Cesar Chavez had focused public attention on the exploitation and desperate plight of the men and women who picked the nation’s fruits and vegetables in blazing heat and biting cold in the fields. They worked for near slave wages, were subject to threats, intimidation, abuse, and even violence. The overwhelming majority of them in the Western states were undocumented workers from  Mexico. The growers shuffled around at will from field to field and when the crop was harvested often dumped them back across the Mexican border.

Mexico. The growers shuffled around at will from field to field and when the crop was harvested often dumped them back across the Mexican border.

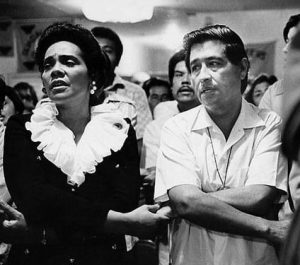

Cesar Chavez, like Dr. King, was not just the head of an organization dedicated to fighting for fair wages and better working conditions for the farmworkers. He was a pivotal and inspirational figure in the civil rights and labor reform movement. What made the interview even more exciting was that Chavez was coming to the Free Press offices. In anticipation of that and to make sure I had my facts straight, I read numerous news accounts, and stories about Chavez and the United Farmworkers. I was deeply conscious that I would be sitting in the same room with a true movement giant.

My first surprise came when Chavez arrived at the offices. He had no entourage, companions, or bodyguards. It was just him and a young aide. He greeted me with a broad smile and warm embrace as if we were old friends who had known each other for years. There was absolutely no air, pretense or assumed importance about him. He was the paragon of modesty and humility. He spoke softly, and in deliberate tones, and he chose his words very carefully.

During the roughly one hour that we talked, Cesar Chavez ranged over many of the issues that were crucial to the farmworkers and their drive to unionize; the low wages, the back breaking labor, the often harsh treatment they were subjected to, the lack of sanitary facilities. Chavez always set this against the guns and clubs that he and union organizers routinely faced from grower sponsored assailants. They were determined to beat back the farmworkers in their long and bitter fight for better wages and working conditions.

Cesar Chavez eagerly praised Dr. King. He made it plain that King was his hero and that he patterned himself and his activist, aggressive emphasis on non-violence after King’s actions. Chavez beamed every time he mentioned King. He mentioned him often. He had a near devout gaze as he recalled to me the telegram that he had received from him in September 1966, in which King wrote, ”You and your valiant fellow workers have demonstrated your commitment to righting grievous wrongs forced upon exploited people.” Chavez made clear that he had regarded King as his teacher and they shared much in common in the tactics and goals they employed.

It was a great moment for me listening to Chavez pay tribute testament to King. He rose slowly at the end of the interview and walked slowly to the outer office. He paused for a moment, quietly thanked me, and shook my hand warmly. As I watched him leave the full impact of being in his presence hit me. The reality that I had sat a few feet from this humble, but powerful figure, gave me an intense feeling of pride. It was the same feeling that I got six years earlier when I stood just a few feet from Dr. King at a rally of religious leaders for civil rights at the L.A. Coliseum.

King and Chavez! I had seen and heard both, up close. Now I knew why these two giants in the fight for justice and equality had a symbiotic bond and kinship. Their names were linked together and I was sure the relationship of the two men, their ideals, and their fight, would stand the test of time. It was indeed a true mark and testament to their work that both would be honored with holidays in their name. The national holiday for King comes the third week of January. Chavez is honored with a state holiday in California on March 31, and an optional holiday in states such as Colorado and Texas. Celebrations for him are held in many other parts of the nation.

I saw and heard Chavez several times over the next few years. Nothing had changed from the day he sat across from me in the small office at the newspaper for the interview. I was always moved by the warmth, humility and soft spoken measured manner in which he spoke. The burning passion and conviction and absolute iron determination he had to win justice and equal treatment for the farmworkers.

Following his death in April, 1993, his widow donated his black nylon union jacket to the National Museum of American History which is a branch of the Smithsonian. He was 66. This was the same jacket that Chavez had with him when he came to the Free Press offices for our interview two decades earlier. The jacket symbolized his and the farmworker’s quest to advance the cause of social justice in America. Now it belonged to the nation.

Columnist; Earl Ofari Hutchinson

Official website; http://twitter.com/earlhutchins

Leave a Reply